by Letha Dawson Scanzoni

(Copyright 2011 by Letha Dawson Scanzoni)

Before I continue with the backstory of All We’re Meant to Be, I am reproducing below what Nancy Hardesty  and I wrote in our respective essays for the preface in the first edition (Word Books, 1974). Both essays not only sum up in more concise form the story told in my Part One post, but a close look at the prefaces reveals at least four things that are of interest as we look back on it so many years later:

and I wrote in our respective essays for the preface in the first edition (Word Books, 1974). Both essays not only sum up in more concise form the story told in my Part One post, but a close look at the prefaces reveals at least four things that are of interest as we look back on it so many years later:

Looking for answers. It is clear that Nancy and I were in process. We were approaching the topic not as experts on how equality could be achieved between males and females, but as seekers. As we did our research, discussed, and wrote about what we were learning, we were often seeking and finding answers to our own questions and then sharing them with our readers.

Our questioning of social norms and expectations. Even though we were questioning and challenging societal expectations for women and men during the time we were writing, we were to a considerable extent caught up in some of those expectations ourselves. Nowhere is that clearer than in the last lines of the closing paragraph of my preface (for which I’ve been criticized) which show my acquiescence to the social norm that both husbands and wives in heterosexual marriages took for granted, namely, that it was the wife who bore the responsibility for household tasks and childcare — no matter how much her life was otherwise filled with career responsibilities, educational pursuits, writing a book, or anything else. According to society’s rules, her other pursuits were only permissible if she demonstrated that she first fulfilled those other tasks and fitted the other parts of her life around them in a way that was not expected of husbands. I worked very hard to follow that dictum. This was the expectation not only in religious circles but everywhere else as well. (I’ve written about that on 72-27, the cross-generational Christian feminist blog that I write with Kimberly George. You can read my descriptions of life and gender-role expectations in the 1950s and 1960s here and here.)

The language issue. Although Nancy and I tried to avoid using male pronouns generically to apply to both males and females as was still common practice in the United States, a few slipped through in various places. (An example: “Why should a person’s sex organs be any more relevant to his holding power than his skin color, his ethnic origin, or his religious affiliation?” [p. 85, in All We’re Meant to Be, first edition].) We even justified it on the basis of grammatical convention. Society was only beginning to question that convention and awaken to the importance of inclusive language, and we were still rubbing our sleepy eyes and not yet fully awake to the symbolic significance of the issue ourselves.

We also, in this first edition and in our own thinking and speaking for the most part, continued to follow the customary use of male pronouns for God, as can be seen in both of our prefaces below. But at the same time, we broke with tradition in even bringing the matter up at a time when few Christians were addressing the issue at all. In our chapter on understanding and interpreting the Bible, we emphasized that “God is neither masculine or feminine” but is Spirit, and we showed the many ways female imagery was used for God throughout Scripture. Still we did not follow this awareness to its logical conclusion and instead followed what was considered proper grammar at the time! We wrote, that the terminology we used for God was “not intended to indicate sexuality but generic personhood. . . . Usually in referring to members of a group or a person whose sex is unknown, we use the masculine. It is generic, whereas the feminine is used in reference only to individuals known to be female. God is neither or both. He contains all personhood: we are all made in his image, male and female” (p. 21).

When the book was published in the late summer of 1974, the publisher sent us on a limited publicity book tour, with some of the media appearances featuring both of us together in some cities and some arranged for each of us separately. Nancy and I recall having had some disagreements over how much to say about the God language issue and how far to push it, knowing how controversial that issue was (and still is) among many Christians. Our book was already stirring up controversy in its basic premise that called for full equality for women and men in all areas of life.

By the time the first paperback edition was published a year later, we added a study guide ( the only change in that edition), in which we asked, “What does it mean to say that all language about God is metaphorical?” We went on to discuss the issue more fully in that study guide section, including writing about inclusive language in hymns, liturgies, and Bible translations, and recommended a number of books and inclusive language guidelines. This 1975 edition was the only edition of the book that contained a study guide.

the only change in that edition), in which we asked, “What does it mean to say that all language about God is metaphorical?” We went on to discuss the issue more fully in that study guide section, including writing about inclusive language in hymns, liturgies, and Bible translations, and recommended a number of books and inclusive language guidelines. This 1975 edition was the only edition of the book that contained a study guide.

After the book went out of print at Word Books, Abingdon Press reissued it in 1986 in a revised edition. In that edition, we not only made sure that the text was inclusive (both in references to people and in the avoidance of male terminology for God) but also included a special section specifically devoted to what we titled “The Language Issue.”

After the book went out of print at Word Books, Abingdon Press reissued it in 1986 in a revised edition. In that edition, we not only made sure that the text was inclusive (both in references to people and in the avoidance of male terminology for God) but also included a special section specifically devoted to what we titled “The Language Issue.”

That section began with this sentence, “The major reason that we chose to revise this book rather than simply reissue it was because of our naïveté concerning the language issue in the first edition.” We wrote:

“Many people think that the language issue is trivial; we did at one time. But the passion which the issue generates belies that conclusion. . . .Indeed, since our thoughts and our theology are expressed in language, changing our language affects every bit of our thinking to the core. Changing our theological language to include the female is a most radical proposal since all ‘official’ theology to this point has not been‘objective’ as men would like to have us believe, but masculine in authorship, content, and premise. The female has been excluded not just by grammatical conventions but by the authors’ intentions. And most of us have gotten the message, at least subconsciously.” (pp. 32-33)

A year after that red-cover edition of All We’re Meant to Be came off the press, Nancy’s own very helpful book on the topic, Inclusive Language in the Church was published (John Knox, 1987), which complements our book nicely. And more recently (2010) she wrote “Why Inclusive Language Is Important” for the Christian Feminism Basics section of the EEWC-Christian Feminism Today website.

After the 1986 edition of All We’re Meant to Be went out of print, we extensively revised and updated it for a new edition published by Eerdmans in 1992. We continued to make sure that the language was inclusive throughout and that the language issue was discussed. The 1992 edition was the last edition of All We’re Meant to Be that has been published; and although it, too, is now out of print, copies of it and the earlier editions are available through various sources online.

for a new edition published by Eerdmans in 1992. We continued to make sure that the language was inclusive throughout and that the language issue was discussed. The 1992 edition was the last edition of All We’re Meant to Be that has been published; and although it, too, is now out of print, copies of it and the earlier editions are available through various sources online.

Friendship. The fourth and final observation you may notice in reading the 1974 prefaces below is the emphasis on friendship. By the time Nancy and I wrote our respective prefaces for that first edition, we each realized that coauthoring this book had been more than an intellectual journey through biblical, theological, historical, sociological, psychological, and anthropological sources as we researched gender roles and relationships. We found that along with the practical applications of what we had found, our coauthorship had also provided us with an unexpected gift — the gift of a deep, rich, long-lasting friendship (over more than four decades at this writing and through many changes in our lives). And it provided a sense of Christian feminist sisterhood that expanded in ever widening circles with the formation of the Evangelical Women’s Caucus that same year that our book was published. Nancy and I talked about writing a book on friendship as our next book project, but unfortunately we never did.

Here now are our two prefaces, published in that first edition of All We’re Meant to Be: A Biblical Approach to Women’s Liberation:

Letha Dawson Scanzoni’s preface to the 1974 edition of All We’re Meant to Be

Several years ago, after observing reactions of fellow Christians to some of my views on woman’s role in the home, church, and society, it occurred to me that all too little creative Christian thought had been given the subject. The phrase “women’s liberation” was not yet in use, but stirrings indicating a new surge of feminism were apparent. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was on the bestseller list, and articles on “trapped housewives” were beginning to appear in the popular press. Yet, for the most part, it seemed that Christians were sitting on the sidelines saying nothing about the “woman question”—except to voice dismay at the way things were going and to warn of dire consequences for society if women were to forget that their place is in the home.

The idea of writing a book on the subject began to grow in my mind, and I wrote a few articles on woman’s role in Christian perspective for Eternity magazine. Reader reaction varied, but I was especially encouraged by the interest shown by an assistant editor, Nancy Hardesty. We corresponded only briefly and infrequently; but from the clippings she sometimes sent for my files, I perceived that we had similar viewpoints. The thought of inviting her to join me as coauthor of a book about women flashed through my mind. But I dismissed it, thinking she was too busy with her editorial responsibilities even to consider it. I laid the project aside to accept other writing assignments.

In 1969, a visit from an unmarried missionary friend rekindled my interest in the projected book. She freely confided her heartaches, struggles, and questionings and urged me to write on the woman issue and especially to include some help for single women. Again I thought of Nancy. She had once recommended a book dealing with this topic, and I knew she must have thought a great deal about singleness on the personal level.

However, I debated about writing her. For one thing, I hesitated to invite someone I didn’t even know to join me in such a major project. Also there was the matter of timing. In spite of my writing activities, something of the “restless housewife problem” was creeping up in my own life. I felt this might be the time to return to school to complete my interrupted college education and wondered about the wisdom of getting involved in writing another book. On the other hand, perhaps the book would be just the outlet I needed.

I asked the small group of Christian friends who met weekly in our home for prayer and sharing to pray with me for God’s guidance. I then planned to write to Nancy Hardesty and ask if she would like to join me in writing such a book. At the same time, I would investigate the possibilities of applying college credits from years before to a degree in religion at Indiana University. Whichever of the two paths opened up I would accept as God’s leading. I never expected both to be his answer—but that is what happened.

God’s timing was perfect. Unknown to me, Nancy had just moved to the Chicago area, only a five-hour drive from my home, making it possible for us to meet soon after I wrote her and to have many delightful visits together since. I expected to find in her a writing partner, and I did. But more than that, I found a friend. And sister. During my year of completing my university studies, she stood by me with constant encouragement and faithful prayers. She also tried to help me work through the many practical problems of combining family responsibilities with the time and energy demands of a writing career, just as I’ve tried to help her work through the challenges of living as a single woman in a couple-oriented society. Both of us have come to understand the “woman issue” in a broader and deeper sense than ever before, in relation to both married and unmarried women, because we have learned to understand, love, and appreciate each other.

Special thanks are due to my husband John who encouraged us all the way. We are grateful for his willingness to serve as a sounding board for our ideas and for the many research suggestions he gave us. (It helps to be married to a sociology professor who is also doing research and writing in the area of women’s roles!) And we want to thank him for those times when, during Nancy’s visits, he somehow managed to put up with two “liberated women” whose long talkathons sometimes lasted until two or three in the morning and whose engrossment in putting together the book sometimes seemed to take precedence over putting together his dinner! But he bore up well, as did sons Steve and Dave. Our thanks to all three.

–Letha Scanzoni (then living in Bloomington, Indiana)

Nancy A. Hardesty’s Preface to the 1974 edition of All We’re Meant to Be

The year 1969 marked a turning point in my life. Bitter about the way my life was going and homesick for the Midwest, I agreed to take a teaching position at Trinity College in Deerfield, Illinois. This involved two things I had vowed never to do: teach, and work for another Christian organization.

During my first frustrating month I received a letter from a woman I had never met and knew only by name from her writing, Letha Scanzoni. She asked if I were interested in joining her as coauthor of a book on women. She warned me that the project was a lonely and controversial one, but suggested that we seemed to have the same views and so might stimulate each other’s thinking. In my reply I warned her that I was no longer a professional writer but an “old maid schoolteacher” and had no answers to the problems of singleness. But I accepted the offer to share the search for some answers to the whole “woman question.”

As Robert Frost says in his poem “The Road Not Taken,” “that has made all the difference.” In the past few years I have been traveling an entirely different road, one which God set me on despite my own logical calculations to the contrary. I have found that I enjoy teaching immensely—enough to motivate me to go back to graduate school for the necessary Ph.D. My writing career has blossomed in several directions. And my relationship with Letha, nurtured by sometimes almost daily letters and frequent visits, has radically changed many areas of my life.

We have written a book together. It could have been merely an intellectual and business collaboration. Instead it has been a union of two souls. I came to her a bitter, lonely, insecure, frustrated, and troubled person. And I found in Letha someone who was interested not only in my intellectual ideas, but also in the wounds of my heart. I found acceptance, empathy, and love. It revolutionized my life. She has shown me God’s love until I can now truly believe that he loves me. She has understood and supported me until now i can accept myself and step out into new pathways. She has probed and challenged my thinking as I have probed and challenged hers. Together we have struggled with all aspects of what it means to be a woman, married or single, in today’s society.

You have in your hands our answers. We hope that our thoughts will stretch your mind, inspire your spirit, and deepen the love in your heart for all your sisters.

–Nancy Hardesty (then living in Chicago, Illinois)

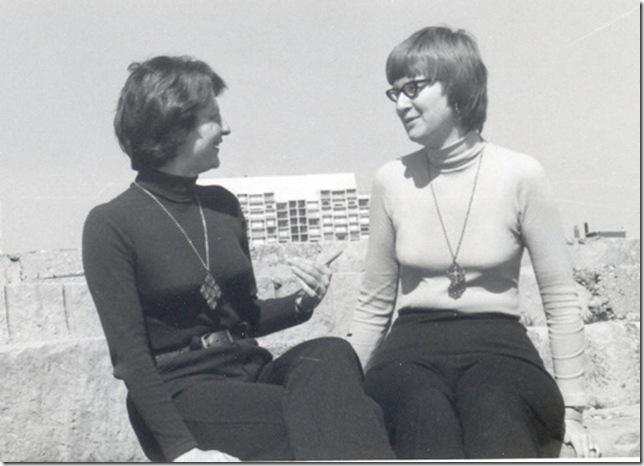

Neither Nancy nor I can find a copy of the glossy photo that was used on the back inside jacket flap of the first edition of All We’re Meant to Be. But my son Steve, then a teenager, snapped this photo along Chicago’s lake shore on the afternoon that he took the photo that was actually used; so this will give you some idea of how we looked on the jacket photo.

on the back inside jacket flap of the first edition of All We’re Meant to Be. But my son Steve, then a teenager, snapped this photo along Chicago’s lake shore on the afternoon that he took the photo that was actually used; so this will give you some idea of how we looked on the jacket photo.

Letha (left) and Nancy (right), spring 1974.

Coming Next

In my next post in this series on the story behind All We’re Meant to Be, I’ll continue where we left off in the previous post (January 7, 2011), with more of our correspondence and a description of the actual process of coauthoring the book together.